Authors: Julia Mynott, Heather McGinness and Lauren O’Brien

Colonial-nesting waterbirds such as ibis and spoonbills, are a unique part of Australian ecosystems and may come together in huge colonies, ranging from tens of thousands, to hundreds of thousands of birds, to breed during flood events. The Murray-Darling Basin is home to several important wetlands that colonial nesting waterbirds use for breeding. When these large colonies gather, and successful breeding occurs, there are many, many mouths to be fed, as all the birds and chicks in these colonies must eat every day.

Have you ever wondered how much food a chick needs to become independent from its parents? And when such large colonies come together, are appropriate food resources available during the nesting period?

Many colonial-nesting waterbirds have developed specialised foraging techniques and adaptations (e.g. the spoon-shaped bill of the spoonbills is perfectly designed for watery habitats) to find and eat their favourite foods. Maintaining water in these wetlands is important to these bird colonies as prematurely, or rapidly falling water levels, are an indicator to the breeding adults that food resources may soon decrease. When adult birds sense that food may become scarce during a breeding event, they may abandon their chicks.

For many waterbird species, the availability of food is related to the extent, depth and duration of flood inundation into wetland areas. With the water inundation into these wetland areas, food resources can flourish (as shown in our recent EWKR Story Fine dining for fish? Wetland and anabranch systems offer the ‘best fish buffets’) and the basal resources promote these systems to provide increases in the preferred food sources of waterbirds, such as fish, frogs, yabbies and invertebrates.

Environmental water is used throughout the Murray-Darling Basin to minimise the risk of chick abandonment for colonial-nesting waterbird breeding events. Locations such as the Barmah-Millewa Forest, the Macquarie Marshes and the Narran Lakes are managed in this way for Straw-necked Ibis (Threskiornis spinicollis), Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus), and Royal Spoonbills (Platalea regia). While the knowledge exists regarding the use of water to manage nesting sites to prevent nest abandonment, there are significant knowledge gaps about the food, energy, or foraging habitat required by colonial nesting waterbirds to enable the adults and chicks to survive a breeding event, and maintain and grow populations. This led EWKR researchers to ask: once eggs survive and chicks hatch, how much energy is needed for that chick to survive? And does this give us an indication of the landscape scale food resources needed during this period?

So how much energy do chicks need?

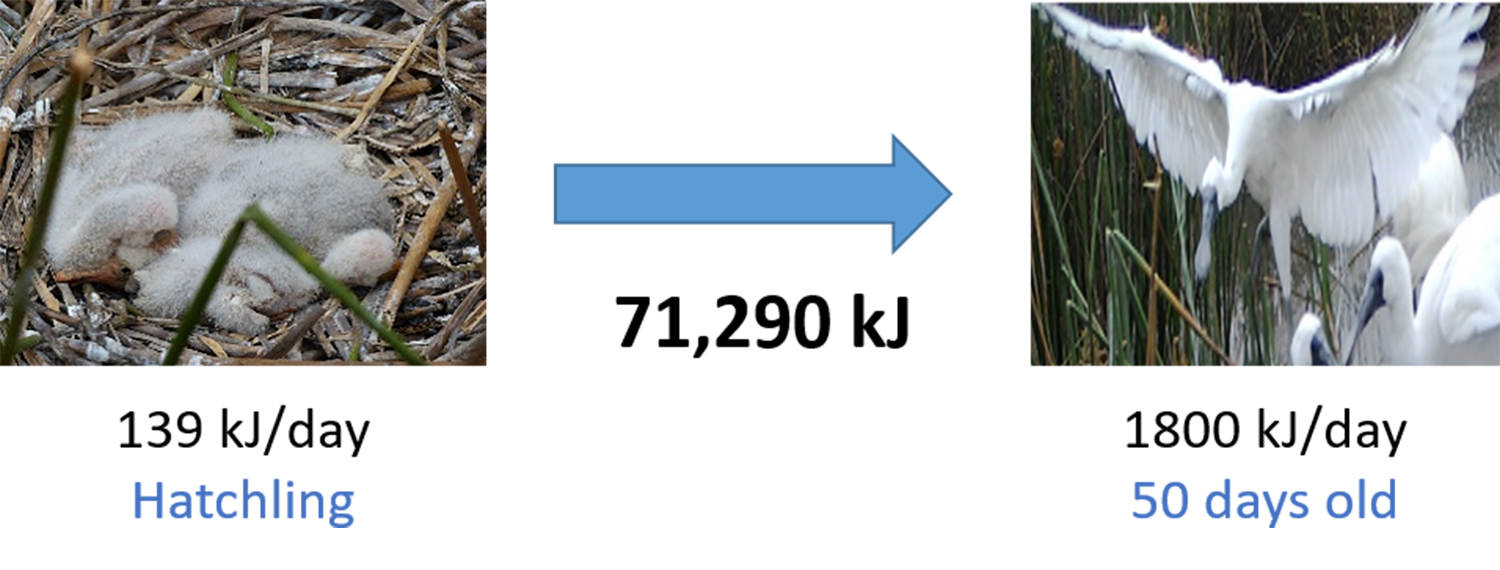

Researchers investigated this for the Royal Spoonbill and Straw-necked Ibis. They found that newly hatched Royal Spoonbill chicks need to be fed food with a total energy value of 139 kJ per day. By the time the Royal Spoonbill chicks can feed themselves (at 50 days), their energy need has risen to 1,800 kJ per day.

Australian White Ibis chicks are a little different, and require less than spoonbills on hatching, with a newly hatched chick requiring 81 kJ per day. By the time the chick is 50 days old, however, they require slightly more than the spoonbill, needing 1,884 kJ per day. The total energy needed to raise a single Royal Spoonbill chick from hatching to independent feeding at day 50 is 71,290 kJ, and for an Australian White Ibis chick is 67,160 kJ.

Note: To put that figure in perspective, the average adult human requires 8,700 kJ per day.

How much food is that?

So, an individual spoonbill chick requires 71,290 kJ to reach fledging, but what does this number mean in terms of the amount of food needed for that one chick, and further, what is needed to support the whole breeding colony?

EWKR researchers used prey energy values to answer that question. A nesting event for either Royal Spoonbills or Australian White Ibis usually has 1000 nests,and produce on average of three chicks per nest. To support these 3000 chicks over the 50 days to independence, the adults would need to provide an estimated ten tonnes of yabbies or eight tonnes of fish! In addition, the parents of all those chicks also need to eat for their own energy needs. Thankfully, these birds don’t eat just one type of food.

What types of food are they looking for?

Chicks rely on the food their parents can bring them, so what are the parents targeting and where are these food resources found?

Royal Spoonbills use their specialised bill to target mostly small fish, yabbies, shrimp, frogs, tadpoles and aquatic invertebrates in shallow water bodies. In contrast, the Ibis species (Australian White Ibis, Straw-necked Ibis, and Glossy Ibis) have quite broad diets, and forage in a range of different landscapes, including aquatic and terrestrial habitats that may be natural or artificial (i.e. cropping or grazing pastures). The ibis eat some of the same aquatic food sources as Royal Spoonbills, but also commonly eat large quantities of terrestrial prey such as locusts, crickets, spiders, beetles, caterpillars and centipedes.

This means that ibis are more likely than spoonbills to find enough food for their chicks when there is a range of different water levels in wetlands and river systems. This is because ibis are less dependent than spoonbills on surface water for their feeding. The implications for water managers is that spoonbills need water for longer in order for their chicks to grow into adults.

Are our current management practices producing this?

Most foraging by nesting adults is done within 2-10 km of nest sites, so a large colonial-nesting waterbird breeding event can place a huge demand on the ecosystems around the breeding site. Remember, the figures above are only for raising chicks – they do not include the food required by the nesting adults, or by juveniles older than 50 days. Additionally, it is likely that adult food needs are increased during breeding periods due to the amount of energy they need to look after their demanding chicks! If we upscale to include adult food requirements and multiple species, a considerable amount of food is required just to complete a single multi-species waterbird breeding event… and what about all the other animals that rely on these food resources too?

In a recent EWKR story Fine dining for fish? Wetland and anabranch systems offer the ‘best fish buffets’ – researchers showed that wetlands and anabranches were producing a lot more nutritious food than the river channel itself. The story showed that the connection to the river channel was very important for larval and juvenile fish to access to the rich amount of food resources in wetlands. This connectivity often requires environmental flows to establish and maintain these links. For waterbirds, the potential for a rich food resource in the wetlands and marshes where they forage may increase breeding success and, if the timing is right, then a fish buffet might provide the energy requirements they need to support chicks through to fledgling and, hopefully, into adulthood.

The key take home message of this work is that appropriate inundation and management of wetlands and anabranches is critical for the support of waterbird breeding events, not just to minimise the risk of nest abandonment, but to enable adults and chicks to survive. To optimise the ability of adults to forage through the chick rearing period, environmental water managers need to consider staggering environmental flows so that not only the river channel, but wetlands and anabranches, are inundated over several months when the energy requirements of waterbirds are at their highest and multiple food sources are required.

For further information:

- contact Heather McGinness: heather.mcginness@csiro.au

- visit the CSIRO project website, or our Facebook and Twitter page

Related links:

The EWKR Waterbird theme is led by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

The EWKR Waterbird theme is led by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).